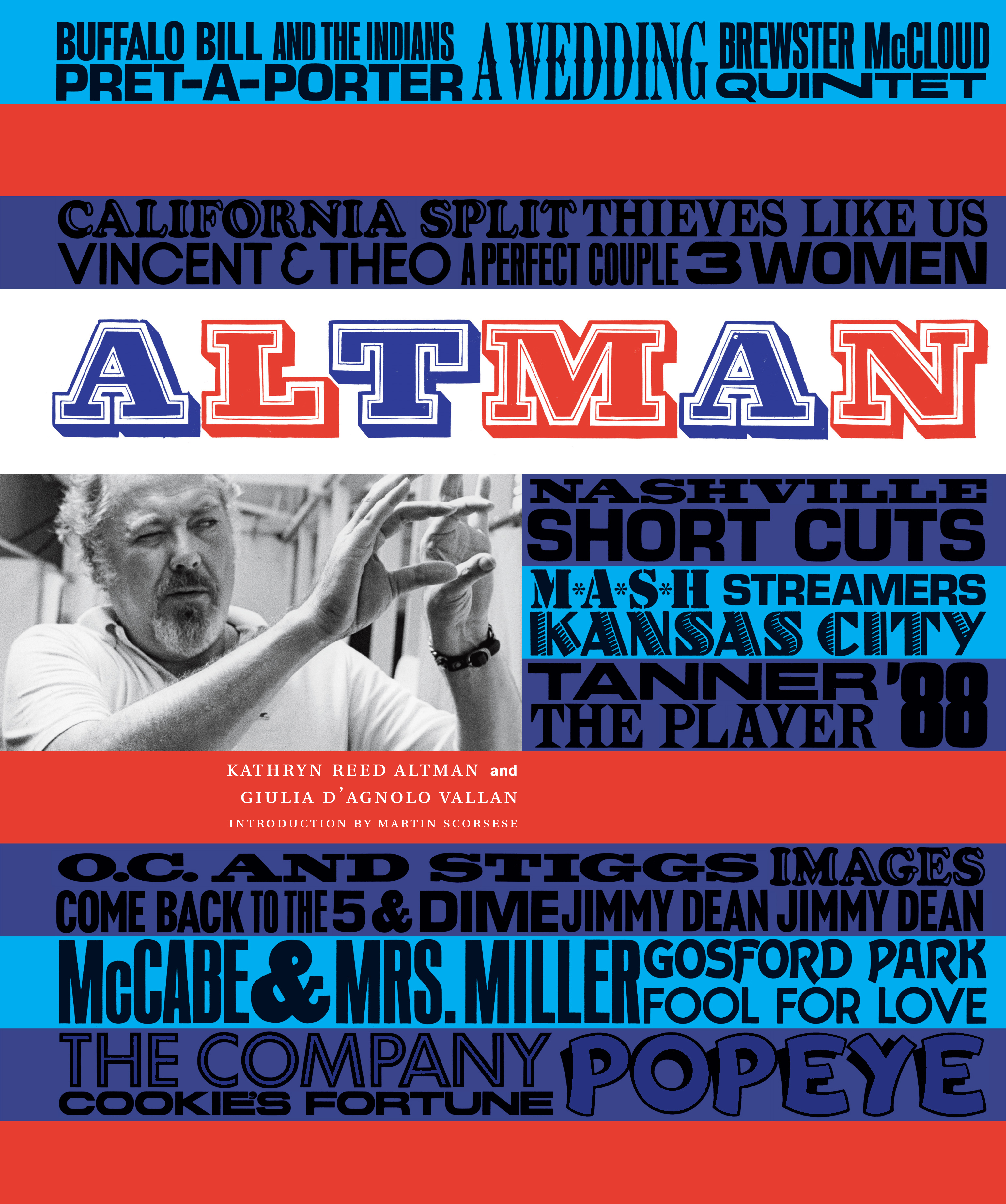

So much of Robert Altman’s career seems just simply impossible, be it the decades of evolving yet consistently quality work, or the effortless weave between genres, or maybe the ability to create a film that utilizes the talents of both Meryl Streep and Lindsay Lohan. Perhaps most unbelievable of all is that it took this long for the filmmaker and his work to be celebrated in a glossy, full-color book, aptly titled Altman, befitting of the best bookshelf real estate.

Considering the director’s career, a 334-page coffee table book seems like a mere glimpse into the full Altman canon, and co-authors Kathryn Reed Altman and Giulia D’Agnolo Vallan would probably agree; in fact, in the book’s introduction Vallan likens it more to a scrapbook. If the book is a WWE wrestling match (bear with me) and each round takes on a decade of Altman’s career, Vallan tackles the critical and contextual elements and then tag-teams Altman (the director’s widow) for personal insight and family photos.

The guest stars in the book offer a diversity befitting of the man, including contributions from Julian Fellows, Martin Scorsese, Jules Feiffer, Gary Trudeau, Roger Ebert, Garrison Keillor, and other voices of film and cultural royalty. When such a treasure trove is unleashed upon the cinephile community, there’s bound to be some gems that stand out more than others. A small sampling includes: the costume continuity sheet for Nashville (Shelley Duvall mastering the endless supply of kooky-krazy-hippie-druggie looks thrown at her); a collage of individual Short Cuts cast member portraits (it needs to become the wallpaper for my non-existent guest-room); and the documentation of a limited edition Swatch watch designed by Altman, featuring a clean white face that in lieu of arms simply says “Time to Reflect” (the watch currently retails on on eBay for $125).

In an essay penned by Kurt Vonnegut Jr., he confesses that Altman’s films make him question his entire mistrust of modern machinery — a compliment if ever one existed. As Vonnegut puts it, “Robert Altman has used the camera to produce a ribbon of acetate that, when illuminated from behind, projects onto a flat surface in a darkened room anywhere a shadow play of what we have truly become and where we might look for greater wisdom,” which is Vonnegut’s less succinct but more poetic version of “two thumbs up.” James Franco, who was featured in the Neve Campbell-produced, Altman-directed film The Company gives a surprisingly touching and insightful look back on his relationship with the late director, who had planned for Franco to star in a never-made drama set in the contemporary art world, an oddly forth-telling example of Altman’s genius for casting.

Altman is arguably the master of the ensemble, so it seems only fitting that a scrapbook be created in his celebration. While the ordering of things in the book can be slightly confusing at times, there’s not an unwelcome page among the 334. Altman is the latest in Abrams’ recent line of coffee-table friendly profiles of iconic directors (previous editions highlighted Wes Anderson and Martin Scorsese). I can’t wait to see who they profile next, but if they’re looking for ideas, Altman’s Swatch watch was part of a series that included Pedro Almodóvar and Akira Kurosawa.![]()