Before diving into The Residue Years, I knew very little about Mitchell S. Jackson. But after getting through a couple of pages, I was instantly hooked by his brutal honesty—and annoyed that I had other seemingly pettier obligations in life, like going to work and sleeping. After devouring the book I wanted to explore the other side of Mitchell’s life story (the aftermath, if you will) which, as you’d expect, is just as captivating as his debut novel. He was kind enough to open up the conversation. —Matthew Lynch

Was it difficult to write characters who were based on real people? Did you feel the responsibility to ask for permission or have them read the manuscript before it went to print?

I found it easy to write about characters that were based on real people. I actually think most writers are doing that. Even if I was writing about Martians, I would be humanizing them, imbuing them with my understanding of humanity. To answer the second part of the question, I did not feel compelled to ask permission. For one, the last thing I wanted was to have someone else’s truth get in the way of my truth. Plus, in a sense, I was telling my story to get at a collective story. There were plenty Champs and Graces I knew during that time. And last, there is much more fictionalizing in the book than most people think. There isn’t one character who is based completely on a real person from my life. All of them are conflations.

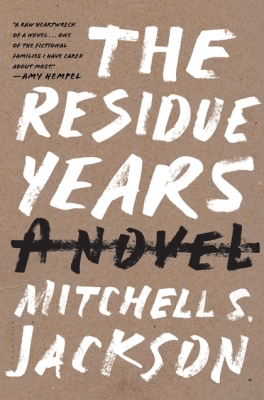

Why did you choose to fictionalize this story as a novel rather than writing a straight-up memoir? (We can’t help but notice that “A Novel” has a bold strike-thru on the book’s cover.)

I wish I could take credit for the strike-thru, but I can’t. That was designer Benjamin Wiseman’s way of suggesting the semi-autobiographicalness of the book. Why wasn’t it a memoir? To keep it 100, when I conceived of writing a novel I didn’t know much, if anything, about memoir. There was fiction and non-fiction. Also, back when the book was closer to my actual experience, I was hesitant to implicate people in explicit ways. Drug dealers were still drug dealers, robbers were still looking for marks. I was hyper sensitive to the fallout possible from flouting hood ethics. Plus, the further along I journeyed in writing and revising, the more freedom I needed to create and not be beholden to what exactly happened.

In an interview you said other people believed in you before you did yourself. Was outside encouragement the primary driving force behind finishing up the novel? What else helped you get over your initial fears?

The encouragement was for me to be something positive. It was what we tell all children, “You can be anything if you put your mind to it.” But outside encouragement wasn’t the driving force to finishing the novel. When I first started no one encouraged me to be a writer. Shoot, no one around me knew what it meant to be a writer and by that I mean what a writer’s life entailed. The further along I got into writing and trying to carve out a writing life for myself, the more motivated I became. It was a reason to sit at the computer and type. It was a reason to read closely. I have always been ambitious, but writing gave me worthwhile place to direct that ambition. On the other hand, the encouragement was fortifying. Hearing people like Gordon Lish and John Edgar Wideman tell me that I could succeed or that my work was getting stronger certainly made me feel more confident. Was I fearful at the outset? I think I was more so ignorant, and because I was ignorant of just how grand a task is writing a strong novel, I had much less trepidation than I should have had. If I had known, who knows, maybe that fear would have paralyzed me.

From getting a second opportunity to work with Gordon Lish, and Bloomsbury, to finding a steady life post-prison, you’ve had some incredible second chances. How have these experiences changed the way you deal with obstacles?

Whew, where would I be without second chances? One, they made me believe in the possibility that second chances actually existed. That was no small task for a guy who had at points in his life felt so fated. The second thing they have done is force me to be patient, to see the value in patience. None of my major goals have happened the way I wanted them in the time frame I wanted. But I think that has made me have a different level of appreciation for each tiny accomplishment. These days, my general attitude is it will happen if I give it time. Without experiencing some of those second chances, it would have been very easy for me to become a defeatist.

What is one important lesson you’d like all your students to leave your classes with at the end of the semester [at NYU, where you teach Creative Writing]?

I want all my students to leave my class with the belief that writing is one of, if not the most, important skill in their academic life. And also that writing is evidence of one’s thinking and can improve the quality and complexity of their thoughts. And last, I want them to recognize that the real writing is in revising.

Do you identify with the notion of being a “black writer” or is that a term that bugs you?

On the one hand, how could I be called anything but a black writer?! I’m a black man and I write. On the other hand, I think anytime someone prefaces what I do with my ethnicity, they mean to subjugate the writing and me. Let’s keep it funky, nobody is throwing around the term “white writer” with any seriousness. Jonathan Franzen isn’t a white writer. He’s just a writer (no knock on Franzen; I’m just pointing things out). If the term black writer wasn’t meant in most cases to be pejorative, I’d say yes, yes, go ahead and use it. But since it does, I often find myself resisting the tag. Give us (black writers) a fair fight out in the world.

Tell us a bit about Oversoul, your next release with Bloomsbury.

I published Oversoul as an ebook a year and a half ago. It included stories and essays. I want to go back in and make it a book-length project. Thematically, it’s going to cover some of the same things as The Residue Years because that’s what I’m drawn to; the fiction will revisit some of the characters in The Residue Years at different points in their lives. I’m excited about it because I love writing in the short form and I also love the personal essay. It’s another chance for me to chase my hero James Baldwin.![]()