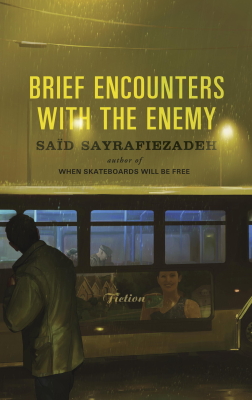

Brooklyn-based Saïd Sayrafiezadeh — essayist, playwright, and author of his memoir When Skateboards Will Be Free (about growing up in the Socialist Workers Party) — has written a gripping collection of fictitious short stories that quietly took me by surprise this year. Top 3! A book of eight stories with interweaving plotlines, Brief Encounters with the Enemy takes you inside the minds of ordinary and nebbish men, almost to a blush-worthy voyeuristic degree. It’s quite a thrill, especially for a ladyreader like myself. Additionally, Sayrafiezadeh‘s writing is comforting and familiar, like being under a warm Cheever-y and Updike-ian Americana quilt. What an honor it was to ask Mr. Trickylastname (we’ll go over this) a few questions! Call me a new fan for life. —JL

Do you think of your characters as tragic?

I don’t think of my characters as particularly tragic, unless, of course, we’re willing to consider everyone tragic (which to some degree we all are). I’d probably pity them if I did, and pity might lead to sentimentality, which is something that I try to avoid at all costs in my writing. The characters in my book are mostly struggling to find their way in the world—that’s a rather vague and general phrase, but “finding one’s way in the world” is often vague and general. They ultimately want something better than what they have—like most of us—whether it be employment, love, sex, apartment. There’s a lot of humor in my characters, some bravado, occasional violence, quite a bit of delusion. In my mind, that’s a recipe for being human. If there’s anything truly sad and pathetic, it’s the world that they inhabit: never ending war and a floundering economy. Does that sound familiar?

What story or character in Brief Encounters do you most relate to?

The opening story, “Cartography,” is based most closely on my life. When I was in my early twenties I was pursued by a lecherous employer in a mapmaking firm. It was one of the first short stories I ever wrote, so it makes sense that I would adhere to true life events. As my writing progressed, though, imagination began to supplant experience, because there’s only so much experience one can draw from. But on some level, I’m sure I must relate to all the characters in the collection (even the lecherous boss!). If they’re emerging from my brain they must have some connection to who I am.

I come across many tender-y books by women writers, many directed right at women readers (not at all a bad thing, but still a thing). Likewise, do you feel like you’re a writer who speaks to the literary man?

I don’t intend to speak to the literary man. Certainly not at the exclusion of the literary woman. I’m not sure who exactly I’m speaking to with this collection, but they’re probably not literary at all. Perhaps it’s the elderly, black man who got on the bus the last time I was visiting Pittsburgh. He must have been seventy years old, and he was missing teeth, and he was skinny, and he had splotches on his face. But when he turned around, I saw that he was actually an old friend of mine, barely over forty, who I hadn’t seen in twenty years. I’m assuming the ravaged face and body was a result of meth. He’d been a handsome basketball player when I knew him, but he’d struggled with a crack addiction, and I remember that he would tell me how he would look at himself in the mirror and try to find some inner strength by saying, “This isn’t for you, Bobby.” Twenty years later, he’d clearly lost the battle. It was shocking and it was sad, and it was, yes, tragic. I wrote these stories with people like him in mind, people who’ll never read my book.

Who or what are some of your own mortal enemies?

Happily, I have no mortal enemies these days. My therapist has seen to that. But during the Iran “hostage crisis” I felt as if my very existence was in jeopardy. That was when I learned well how to view and be viewed as the enemy.

I’m curious to know if you’ve ever considered dropping Sayrafiezadeh since your dad [left home when you were nine months old, to run as a socialist candidate for president in Iran, and] isn’t a part of your personal life anymore. Why did you decide to hold onto it?

I sometimes think about it when I’m having to spell it for someone. It’s such a long, arduous, in some ways ridiculous name. But it was the only connection I had to my father when I was growing up. I kept it all through the Iran “hostage crisis,” and if I could make it through that experience with my name, why change it now?

Furthermore, do you find having an ethnic-sounding name to be a challenge when you hear that people like me (for shame) make quick assumptions about what kind of writing you do?

I generally enjoy the challenge. When I was trying to be an actor it was different, I had to confront the obstacle of my name in more immediate circumstances, i.e., physically standing in front of people who had the power to hire me, but who had already made certain judgements. I was limited by what roles I was able to audition for. The publishing world is different: I have the freedom to define myself. Anyone who reads my books will understand what really lies behind the name.

I know that you’re a fan of COPS, The Office, and Howard Stern from interviews you did in 2009. What stuff are you into these days?

I’m into teaching. And I’m still into The Office (which I watch over and over) and Howard Stern. I had to stop watching COPS, though, because it was too depressing. Speaking of depressing, I saw a recent documentary at Film Forum called Let the Fire Burn about the bombing of the MOVE building in Philadelphia. I try to see as many documentaries and classics as I can at Film Forum. I’ve started going to see live jazz and classical music. Sometimes when I’m listening, I think of how the music is telling me a story. I also play basketball.

As a professor, what one important lesson do you hope all your students leave your classes with at the end of the semester?

Writers are not born, they’re made.![]()