Some musicians record from home out of necessity, others do it because they love the warmth and flexibility. In a world where so much is often out of our control, self recording is a chance to have authority over your own artistic vision — without paying thousands of dollars to rent studio time.

For writer and musician Spencer Tweedy, self recording has come second nature thanks to the influence of his dad, Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, who loaned him gear to start his own setup in the corner of the family basement when he was in high school. Music has also been at the heart of Grammy-winning designer and creative director Lawrence Azerrad’s decades-long career: he’s created iconic album covers like the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Californiation, Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, and the recent vinyl release of the Carl Sagan-led 1977 Voyager Golden Record.

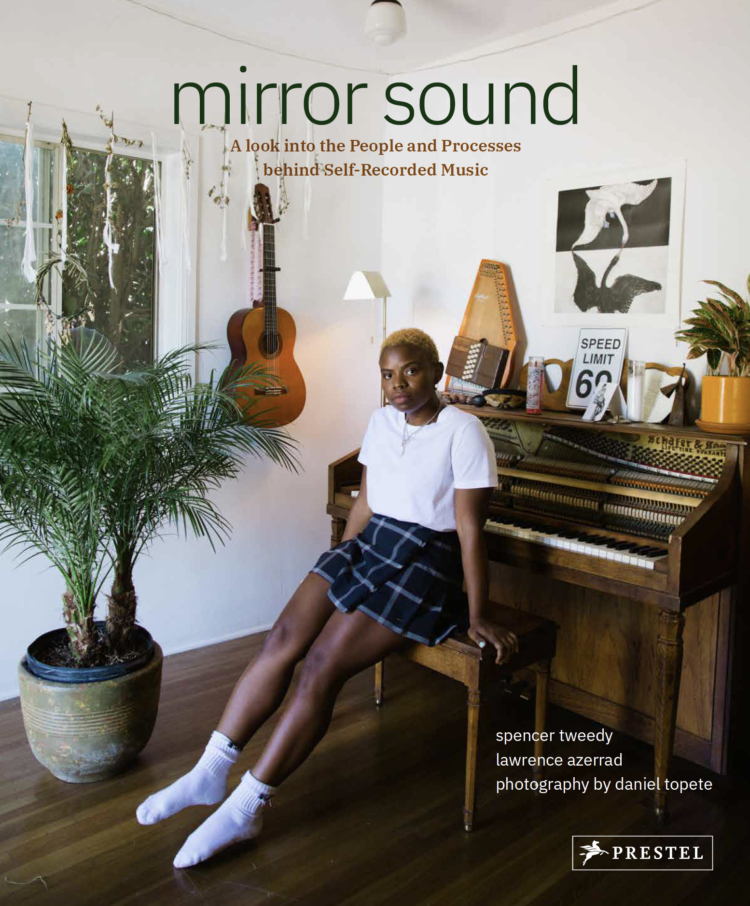

Inspired by the magical singular nature of home recording artists, Spencer and Lawrence teamed up with photographer Daniel Topete to create Mirror Sound: The People and Processes Behind Self-Recorded Music (Prestel), a book complete with intimate portraits, interviews, and personal words by Spencer about his own journey with self-recording.

Reading it, you’ll learn about working with minimal gear with Laetitia Tamko (aka Vagabon, also pictured on the book’s cover), discover the freedom found in making music alone with Melina Duterte (aka Jay Som), sit beside Greta Kline (aka Frankie Cosmos) at the desk where she’s recorded the bulk of her music catalog, and encounter stories from musicians like Bradford Cox, Mac Demarco, Eleanor Friedberger, and more. What emerges from Mirror Sound’s thoughtful combination of words, images, and design is a sacred celebration of artists making music from their comfort zones, surrounded by the tools they know best.

Here, we chat with Spencer and Lawrence about their collaboration, pitching their initial idea to publishers (and refining it after a rejection), and what they hope readers will take away from their new book.

How did the idea for this book begin, and how did you get started?

Spencer Tweedy: It started several years ago when I was getting into self-recording for the first time, learning how to engineer on my own, [and] buying a bunch of affordable recording equipment. After getting a grip on that, I realized that there might be an opportunity to make something related to this discipline of self-recording. There are great things out there about music production — like Tape Op magazine, and Song Exploder podcast and whatnot — but it didn’t really seem like there was something totally dedicated to this weird, global community of people recording at home or recording on their own.

Lawrence and I spoke about it and developed the idea into what it became, with his perspective from music and design, and my perspective having learned how to engineer on my own. We incubated it into a photo book.

Lawrence Azerrad: Soon, it became almost like — between Spencer’s perspective and Daniel’s perspective, and my perspective — a meditation on creativity, even though recording and self recording and home recording is the main channel. It’s this whole idea about self-starting and perseverance and follow-through and creative integrity.

What’s it like to write a book with other people?

Spencer: The creative process was thoroughly collaborative. Mostly, the ideas and the concepts behind the writing were things that Lawrence and I honed in on through just lots of conversations and soul searching, to put it loftily. Once it came down to the nitty gritty of actually getting prose on the page, I was doing that solitarily, but it was all based on the things that we had [developed together].

Lawrence: We baked this idea in the early days, and then we all went into the corners of our own disciplines. Somehow we all came back into the same room and everything ended up fitting together.

Spencer: Lawrence was also very keen to design in response, or in communication with, the words and also with the photos that Daniel had made.

What was the process of actually pitching this book to publishers and getting people on board?

Lawrence: The idea development and the pitch process took a lot of forming; there was a distinct evolution in that incubation period. It was driven more closely towards the recording thesis, and I think that [when] we expanded to look at more ideas about creativity and process and questioning is when we started to get more traction from the book. We also were lucky that we had Daniel involved from the very beginning. His photos were part of our book and our pitches and the pitches we were trying on, visual languages for layouts.

Of course the book didn’t end up looking like the pitches did; originally the book was passed on. I think it reflects a little bit about the content as well as the idea of failure and picking yourself up and refining the idea and not giving up and perseverance and follow through. We did have the help of editors and people on the publishing side of the industry to advise us.

The pitch itself [was] much like writing a song or making a painting — it took a lot of fixing and fixing and fixing until it was something that finally the publisher said, “All right, this is something…” And then even from there, there was a lot of course-correcting, fine-tuning, elevating.

Was there anything especially surprising about that process?

Lawrence: Well, I had a book prior to this one on the same publisher and it was a much smoother process. The topic was much more specific and it didn’t involve a lot of other voices or artists or interviews.

I just felt from the start that this idea was so good. And the concept of these conversations with people were so good that I was surprised that it wasn’t like a blockbuster right out of the [gate]. But it just goes to show, nothing’s given to you and you have to work hard for it.

Spencer: On my end, it was the first time that I had ever been through any interaction with traditional publishing. As small and nimble as Prestel is, they’re still a publishing house. Whereas my only experiences before had been writing a blog or I had put out a tiny little chapbook of 250 copies on my own, that was just as simple as talking to a printer. So it was my first experience with that. It was strange; I don’t feel super comfortable with the world of negotiation and getting into those numbers and sticking up for yourself, but also being reasonable.

Thankfully, there was just lots of goodwill all around. Lawrence also had already worked with Holly, our editor. So that all went, I think pretty much as smoothly as one could ask, but my eyes were wide through all of it. And I was figuring it out as we went along.

The money part of publishing can always be very mystifying and intimidating.

Lawrence: For most people putting out books, unfortunately, it’s not a largely a financial endeavor, unless you want to write a book about organizing or home closets or something like that, or about K-pop. But for us, and for a lot of authors, it was about sharing ideas and with the public and giving something creative to the world. Spencer and I think both through his work in the studio and my work, doing art for music, we both have experience in having a vision and a North Star close to our hearts. But [we also have] experience in feedback and collaboration and bending towards that feedback in the right way that you’re not acquiescing your soul, but also elevating your work through the feedback.

[In terms of how a book is made], I think if you come in from a really rigid point of view, I don’t think that might work too well. But you also have to have something really close to the heart that you want to keep persisting on.

The book is built around so many incredible interviews. Did you have a dream list of musicians that you wanted to speak with and kind of go from there based on who is available?

Spencer: There was a lot of working around the constraints of who said yes and whom we could schedule in proximity to each other to make everybody’s schedules click together. But I think the starting point was a lot of artists that I had existing relationships or acquaintanceships with through playing music and on the road with my dad.

Then we expanded it in the effort to make it not monotonous, and to make sure it wasn’t all guitar music or, and not all white guys. And our editor helped us a lot with that. And we just tried to reach out beyond the people that were already close or obvious to us.

Lawrence: It’s surprising how much a degree of production informs the body and life for the book too. A lot of effort in the year between Spencer and I was spent truly producing with a Google doc, emailing people, sending asks out, and [figuring out] who could do it and who couldn’t do it — just schedule and whatnot. That ultimately ended up informing a lot of what Spencer wrote, and the body of the book. That is an aspect that often goes unconsidered, and it’s funny because editorially or content-speaking, the book is about structuring and process and production.

Are there any favorite memories both of you have from the interviews?

Spencer: Everybody’s space was cool and unique and fun to visit and to learn from them. Some standouts would be Suzanne Ciani in California, because her house is in an amazing place. But also because she was a really amazing person, just super welcoming and entertaining.

The other most memorable for me was Emitt Rhodes, also in California, because he had been, and is, a musical hero to me. And unlike Suzanne, whose space was amazing, Emitt was in the space that he had been in since 1972, I think. It was like getting to walk into the room where a musician I admire made music that I admire, standing next to him. And that was just really unexpected and awesome.

Doing the interviews was one of my biggest areas of anxiety about the project. I have no journalistic training and I was trying to talk to friends of mine who are a lot more experienced with interviewing before heading into those — including Lawrence’s cousin, Michael Azerrad, who’s a super well-respected music writer.

I was super scared heading into those first interviews because I wasn’t sure how to be totally prepared and to get everything we needed. Luckily, I think it largely depends on how giving the interviewees [are], and everybody was super generous and would start sharing stories. So that put me at ease, and gave us a lot to work with.

Lawrence: As I laid the book out, I was struck by how well Spencer diversified his questions out. So you don’t have 27 times, “What’s your favorite song,” or “What’s your favorite technique?”

We worked probably a good part of the year in production, so to speak, and more than that including the pitch. As the stories and the text started coming in, you see it through the writing that Spencer produced and through the straight interviews themselves. You kind of fall in love with the people in different ways and certain types of episodes that people mentioned. These peaks and valleys of experiences and stories and anecdotes form a mosaic, which is really a nice part of the book.

It’s very encouraging to hear how every person has approached self recording differently and made it their own. I’m curious how each of you hope that people will use this book or take it in?

Spencer: What I hope people will do is what anybody does with a visually-driven book first: open it up and see Daniel’s photography and appreciate how beautiful his photography is and how not rote it is. He brought freshness and effort to a discipline that could have been really run of the mill.

If they’ve ventured beyond that, into the words, I hope that they take away some of those ideas that Lawrence has mentioned about creativity — creativity being a part of your life, being accessible, even when it seems like it’s not. If it ends up encouraging people, I think that would be a really wonderful outcome.

Lawrence: The repetition of themes that you see echoed in other people’s stories, without it being redundant, is really beautiful. What Spencer just said is repeated a lot in a lot of other people’s words — that discipline of just doing it and just starting and taking that leap and believing in yourself. Also, knowing that you’re going to be scared. These are all fundamental creative tropes, even though we aren’t specifically talking about self-recording.

I just have to add about Daniel’s photography — I know I’m biased because this is our book — but I’ve been working as a album artwork designer for close to 20 years, and Daniel’s photos are some of the best I’ve ever seen of musicians. I think he does a really beautiful job of capturing a sense of space and soul and it being intimate without it being cloying or intrusive or corny. From a purely compositional aspect, they’re just beautiful, just light and form and composition in the room and the space. Through the words and the photos and the ideas, it’s just this odyssey of creative exploration.

A theme that has come up in the past six or eight months that we didn’t really account for is the idea that a whole world of creativity can be spun from home and self. As we go through this pandemic, even though we certainly started this [book] way before that, an idea Spencer talks about a lot is you don’t need a boss or a big studio or others to bestow credibility on you to do what you want to contribute to the world.

It’s oddly so timely because many people are at home, making things with what they have, making stuff alone. In a way this is a really nice guidebook to have beside you while you’re stuck at home. Spencer, you said you play music and have experience self recording. Was there anything from working on this book that shifted your mindset or looked at that practice from a perspective that you hadn’t before?

Spencer: One of the concrete technical shifts that happened came from talking to Ty Segall about his recording process. Ty and Bob Bruno [of Best Coast] and a few other people start with rhythm tracks sometimes. Ty talked about performing improvised parts on a drum kit for several minutes, the length of a song or whatever, with multiple sections and then composing guitar parts or synthesizer parts on top of that.

It’s not that I didn’t know that that was possible. It’s just that I had never known that anybody built their songs that way and released songs that had been built that way. I had sort of believed in the orthodoxy of composing music on a chromatic instrument, like guitar or piano, and then adding rhythmic stuff to it after that. It’s surprising because my main instrument is drums. I would have thought maybe that would have occurred to me at some other point, but it didn’t. And that was really eye-opening.

Lawrence: There was a chart in our early idea development process I made based on my own feelings and approach to creativity, and when Spencer saw it, he felt it was kind of funny how similar it was to the musical process. This idea that disciplines can be more alike than we might think. Even down to the fact that ProTools and Photoshop look really similar, as far as layers. There are just a lot of similarities, especially as media gets more and more integrated.

Ty Segall by Daniel Topete

Laetitia Tamko, aka Vagabon by Daniel Topete

Speaking of the creative process and the pandemic, I’m curious how you both have been dealing with staying creative throughout this whole time. And if anything has changed for you throughout the past six months or so?

Spencer: I procrastinate on creative projects a lot because they matter so much more to me than other things, like answering emails or whatever. It’s frankly easier for me to spend the day doing managerial type work because it’s clear and it doesn’t demand the really labor-intensive parts of your mind and body, which creative stuff requires.

I feel like over the past six months of quarantine, sort of being forced to be at home more, I’ve been trying to confront some of those self-imposed obstacles or procrastinating tendencies.

Lawrence: You don’t want your art-making to be reactive, but I also feel like challenge breeds really remarkable things that you don’t expect. A really great case is the Instagram show that Spencer’s family has been doing through quarantine; I have a lot of projects that have come out of the challenges of quarantine.

When you put yourself in a constriction that you didn’t expect to creatively, if you believe in what you’re doing, you find a way to still produce and make it work, however you can. Sometimes that challenge can have positive results and be generative. It’s a weird thing for people to be in quarantine when there’s so much suffering and people kind of brag, “I’m so busy.” But the upside of that is there’s a lot of work to be done right now. And art has a way of hopefully awakening people’s eyes to things that maybe we should be paying attention to.

Spencer: If I could just gas Lawrence up for a second, we’ve collaborated enough for me to get a glimpse of his work ethic. That has inspired me; it’s really cool to see his dedication and ability to really set aside time and crank things out in a totally inspired way. Not in a way that is mechanistic, but still totally on time and seemingly at-will. That’s a lesson I took away largely from working on this book, from observing Lawrence from afar.

Lawrence: It’s a beautiful collaboration. The people that you work with — and this goes for the people that are also in the book — they make you a better artist. And that’s certainly the case with Spencer and Daniel.

This interview has been edited and condensed.