Some stories grab your hand and pull you out of your mind into another world; others, barely brushing your skin, make your body shatter and vanish, only to reappear with a new molecular arrangement, into an oddly familiar life. Yelena Moskovich’s stories are this kind. They could use the word “otherworldly” as a middle name, inviting us to meet our own hidden creatures face-to-face and run away with them.

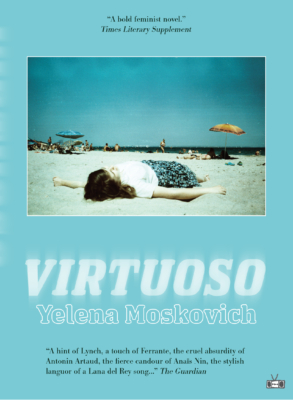

No doubt the Paris-based queer novelist, playwright, performer, and visual artist can teach us a lot about how to move through the world. Born in Ukraine (former Soviet Union) and later emigrating with her family to Wisconsin, Moskovich writes from the fluidity of American English towards a sensual, rhythmic, poetic prose that pushes her fiction to the brink of surrealism. Virtuoso (Two Dollar Radio), her second novel after her acclaimed debut The Natashas, is so far one of my favorites this year. It took me a few pages to realize that to enjoy the novel I had to stop asking how this or that happened, how a love-hate letter to the old Sovietic life fades in and out of a transnational dyke-chat romance. To read Moskovich is to learn how to live and love in an anarchy of plot, form, language, and tradition, but also to understand that it often takes two women to start a fire.

Hi Yelena, how are you dealing with lockdown?

I’m doing good right now and overall, which includes all the phases (first I wrote “phrases”, which is also true) of feeling limited and expanded, weighed down and weightless. Maybe it’s like the lunar cycles on high volume?

Has your creative routine been affected?

With the huge shift in my capacity for focus, I’ve (re)discovered the pleasure of micro-expressions, collage work, dancing, mixed media. I’ve found myself more than ever seeking counsel from my body for creative impulse. Even for expression that does not end-result in the body.

For example, I’ve been working on my third novel throughout confinement. I’ve found that I’ve needed to engage with the novel tangibly, physically, through drawing, scribbling, movement, and so on.

Virtuoso is a multiplot novel with multiple queer narrators. Who was the first character you imagined?

As soon as I finish a novel, I seem to have a sort of amnesia of its origins. I always have a hard time remembering how things began. But I believe it was with Jana and Zorka. Zorka’s eyebrows, in particular. I remember writing the line, “Zorka, she had eyebrows like her name,” and suddenly feeling the whole trajectory of her. Not to say that I “knew” what was going to happen plot-wise, but I had a very strong sense of who she was and who she was not allowed to be.

How has your approach to writing Virtuoso changed from your debut novel, The Natashas?

The Natashas was my first novel and my first true attempt at long form prose. Since my background before that was in theater — writing and directing plays, also movement and body work — I approached writing a novel in a very open, lawless way. I had the bravado of my naivete of the form. I also had a great lack of self-censorship. That is to say, I did not know much about novels, either as a reader or as a writer. Most of my prior consumption and creation consisted of plays and poetry or performance. I wrote freely and it felt like dancing. I felt very light on my feet.

With the second novel, I had already made the rounds, so to speak. I didn’t have the same innocence. I had reviews, critiques, feedback. Some felt inspiring. Some felt limiting. I had to navigate my creativity with those things on my shoulders. But also I became a bit more interested in the craft itself. I became more self-aware. Like a dancer who really studies her own joints and muscular flexions. I wasn’t just in a state of magic anymore, but more a meta-magic, one that is able to reflect on its own phenomenology.

Does theater have a specific significance in your prose?

Definitely. Theater as a space for earth, heaven, and hell. Theater as a false space, a space for communal belief and disbelief. The intimacy and interactivity with the viewer/reader. The spatial language: ways to tell stories through movement, dynamics, incantation, sensual narrative. These are all things that I take with me into prose.

Virtuoso was first published last year in the U.K., and now it’s reprinted in the U.S. by Two Dollar Radio. Do you think American readers might be experiencing your novel differently than European readers?

Absolutely. I think the themes of immigration, queerness, and female sexuality. have a different historical context and current vocabulary in different parts of the world.

For example, if you look at the States right now, there is an understanding of the intersectionality of human rights. The fact that one cannot separate Black rights from queer rights from immigrant rights, etc. It seems to me that in Europe there is a larger pull of denial at the systemic and intersectional reverberation for minority groups. I feel like there is a sort of refusal to be able to see the link between current social struggle and historical injustice.

Many of your characters in Virtuoso come to terms with their sense of cultural dislocation just as they develop their queer identity. How would you describe your approach to queerness as a literary discourse, and is it related to a sense of global identity?

The narrative of Otherness is not just about the subject (immigrant, queer, etc). It’s about form, it’s about recreating language, it’s about redefining the mechanisms or essence of storytelling while telling a story. I think that’s why experimental forms of art and literature have risen after catastrophic global wars or violent periods of political restructuring.

Think about the Russian avant-garde movement reaching its height during the Russian Revolution, or the European avant-garde coming in waves around the First and the Second World War, and so on. In these moments, we get a glimpse of a human experience or even a conceptual experience we don’t yet have a language for — so we create it.

Ivorian playwright Koffi Kwahulé wrote, “In order to not suffer this language, I have to make it resonate differently.”

In this same way, queerness as literary discourse is not just about the subject of queerness, not just about queer people and their stories (though these are very important), but in the context of literature or art, it’s also about the aesthetic language that gives voice and body to the subject. This includes the craft, the form, and the mechanisms of transmission within a work of art or piece of literature.

Your main characters stand for nontraditional attitudes towards sexual and romantic relationships. Do you think it is still hard for a writer to deal openly with alternatives to monogamy or to the classical expectations of romantic love?

I think it’s very hard for all of us, and particularly anyone from a minority group who’s humanity has been devalued, not only to express but to find form for our desire. The forms of partnership that exist have their roots in private property, economy, and state preservation. It is not surprising that they are failing us when it comes to wanting to create partnerships, families, or communities that are rooted in other notions like understanding, respect, reciprocity, personal growth, liberated desire, etc.

That is not to say that it’s as simple as heralding non-monogamy or otherwise. But it is about looking at our expectations of love, partnership, and desire, and being able to see how those expectations are affecting the way that we feel most: free, loved, energized, connected, desired.

Queerness is not just about sexuality, it’s also about theory and social change. Writing queer love or lust or partnership is also making room for a different mindset and a different way of life.

You emigrated to the U.S. from Ukraine as a child, then moved to Paris in your 20s, where you’ve lived for almost 14 years. How has this composite sense of identity influenced your writing?

I’ve definitely gained a lingual agility and vernacular fluidity from moving through these various countries, languages, and cultures. English (particularly American English) is such a wonderfully supple, flexible language. I love using English as a way to hold many languages, playing with structure and vocabulary and conjugation in ways that stretch it, bend it, twist it to my delight.

There’s still some skepticism towards transnational art, especially when it’s made by artists in large cities who may be projecting a fantasy of cosmopolitanism. Do you feel any kind of responsibility in writing about life in the Soviet Union from a distant space and time?

Absolutely, there is a lot of fetishizing of the immigration experience and the cosmopolitan experience.

I don’t feel it as a responsibility because I don’t believe in making art from a place of responsibility (though moral duty and otherwise are valuable things). As I see it, it’s always the marginalized or minority groups that are expected to write “out of responsibility” for their history or culture, while the majority groups get to make art without any expectation that it serves a higher purpose — sometimes in the name of… joy! A privilege that doesn’t seem to extend to people of color or LGBT writers, for example.

I wrote about the post-Soviet diaspora because it gave me joy. Both to write it and to read it. There is not a lot of post-Soviet queer lit (at least not to my knowledge) and it’s such a pleasure to create and to have in my life.